[ Jayeeta Bhattacharya, post graduate in English, and teacher,

is a poet who writes both in Bengali and English. She is the first

female author who has written a Bildungsroman novel in Bengali. ]

Jayeeta : Poetry or prose -- in case of prose critical

essays or stories and novels -- which do you prefer writing ?

Malay : I do not have any preference as such.

Depends on what is happening in my brain at

a particular time. Critical essays I mostly write on

the request of Editors. These days I dislike writing essays ;

actually, since essay writers are only a few,

Editors request for essays ; in many cases

Editors even select a specific subject and request

me to write on it. Is it possible, tell me ?

Now a days I do not like to read much or

think about the society. I write fictions,

once something strikes me I start writing,

there is no dearth of material in my experience,

I may pick up scores of characters from my own life.

When an Editor requests, I send him.

Poetry is really an addiction ; once the grug grips you,

there is no way out other than writing.

I write them on the body of emails ;

when someone requests for a poem or poems,

I mail him. If it is not to what I had intended to achieve

I delete it completely. In fact whoever requests,

I send him, without any preferences.

Some editors identify a subject and request me

to write on it. That creates a problem for me,

as you know I do not write subject-centric poems ;

I write as I please, whether it is liked or not.

I do not have anything like a writing diary or pages,

after 2005, because of arthritis I suffered induced by

wrong medicines after angioplasty.

Then I started suffering from asthma, hernia, prostate,

varicose veins. Because of arthritis

I was going out of writing habit,

you would not be able to feel that suffering.

Texts kept on creating vertigo of thoughts and

I was not able to write anything.

Then my daughter encouraged me to learn

computer, I learned typing in Bengali,

the middle finger of right hand is less affected,

I use it for typing. My son has gifted this computer,

he cleans it whenever he visits on holidays.

For about three-four years I was not able to

write because of problems with my fingers.

Jayeeta : While reading your novels one

finds that the narrative techniques and forms

are different from one another.

From Dubjaley Jetuku Proshwas to Jalanjali,

Naamgandho, Ouras, Prakar Porikha,

have almost the same characters you

have proceeded with, it may be called a single novel,

but you have kept on changing the form and technique.

Why ? Then in Arup Tomar Entokanta novel you

have introduced a new technique,

you have displayed three types of Bengali diction.

In Nakhadanta novel you have put together

several short stories along with your daily diary.

Tell us something about these. Are they conscious effort ?

Malay : Yes. No editor would have published such a

large novel comprising of five, obviously I

wrote them at different periods, each separate

from the other. Dubjaley is written based on my co-workers,

I had learned that some of them are Marxist-Leninist.

Writing five different novels was a sort of boon for me,

I have tried to bring in novelty in all of them.

When an idea comes to me I think about its

form for quite some time, about its presentation,

then I start writing. Quite often a form develops

at the time of writing itself, such as in Nakhadanta or

Arup Tomar Entokanta. While writing Nakhadanta

I had gathered substantial information during field

studies in West Bengal about the jute cultivators

and jute mills. Similarly, for writing Naamgandho

I collected field information of potato cultivators and

cold storages in West Bengal. A large number of

characters in these two novels are from real life events.

I have written outside of my experience as well such as

Jungleromeo, based on beastiality of a bunch of criminals.

I have written the fiction Naromangshokhroder Halnagad

in one single sentence, this is also imaginative,

based on political divisions in West Bengal.

Hritpinder Samudrajatra is based on the voyage of

Rabindranath Tagore’s grandfather’s heart ripped off

from his body in a cemetery in England to Calcutta

in a ship of those days ; I have criticised Rabindranath

and his father in the fiction. Had Rabindranath’s

grandfather lived for another ten years the industrial

scene in West Bengal would have been developed.

Idiot Bengalis of those days attacked his character of

vices which you would find thousand times more in

today’s Indian industrialists, among whom there are

thieves, black marketeers, smugglers and even those

criminals who have fled the country. I wrote the detective

novel as a challenge, but I have dragged Indian society

there as well. I am not able to write a fiction without

involving Indian politics and society. Even the

lengthy story Jinnatulbilader Roopkatha which

have animal and bird characters, is based on

political events a personalities of West Bengal.

Rahuketu is based on court case and activities

of members of the Hungryalist movement.

Anstakurer Electra is about sexual relations

between father and daughter. I have written

Nekropurush deriving on necrophilia. Chashomrango

is about elasticity of time.

Jayeeta : Do you think Salman Rushdie

is the ideal Postmodern novelist in the perspective

of Postcolonial or Commonwealth literature ?

Malay : Rushdie is a magic realist novelist,

influenced by Marquez. However chaotic it might be,

the reader understands the novelist, just like

in the case of Satanic Verses. American critics

do not give much importance to magic realism

because the technique was not invented

in their country ; as a result magic realist writers

are also labelled as postmodern by them.

Though there are certain subtle usage of

postmodern features in Rushdie’s fiction it

would be incorrect to call it postmodern.

If you call fictions of Gabriel Garcia Marquez

as postmodern, spanish critics may shoo bulls

of bullfight at you.

Jayeeta : In your fictions we do not find

conventional trope of love. There are no stereotype

protagonists. Have you adopted these in

order to individualize your fiction as yours ?

In Dubjaley Jetuku Proshwas novel,

Manasi Burman, Shefali, Julie-Judy ;

in Naamgandho novel Khushirani Mondal ;

in Arup Tomar Entokanta Keka sister-in-law,

Itu in Ouras, they are different from

one another and none of them are

stereotype character. You have even

created a shock at the end of the fiction

by revealing that Khusirani Mondal was

kidnapped from East Bengal during partition

and she is actually grand daughter of

one Minhazuddin Khan. You have played with

self-identity in case of Khushirani Mondal ;

without knowing her own origin she recites

songs in praise of goddess Lakshmi, follows

Hindu fasts, believes in superstitions like Chalpara .

I would like to know the intricacies of Malay’s fiction in detail.

Malay : That is because my love life has

not been conventional. Secondly, the concept

of central character was brought to the colonies

by Europe, as a symbol of metropilitan throne.

Women elder to me have first entered my life.

That might be the reason for the ladies being

elder to young men in relationship in my novels.

In female characters obscurely there is presence

of Kulsum Apa and Namita Chakroborty.

The life I led during the Hungryalist movement

has left its impact on female characters.

Through Khushirani Mondal I have tried to

indicate that how problematic is the idea of identity.

Look at today’s Indian society, because of

identity politics the society is getting fragmented,

skirmishes are taking place daily,

Dalits are being beaten up,

Muslims are being driven out of their home and hearth.

By banning beef livelihood of hundreds of families

have been destroyed, Posrk is banned in Islam,

but in Dubai malls you’d get shop corners in which pork is sold.

From identity politics we have reached jingoism.

Let me tell you about my marriage ;

I had married Shalila within three days of proposing to her,

both of us liked each each other at first sight.

I have written these incidents in my memoir.

Shalila’s parents died when she was a kid ;

I am unfortunate that I did not get the affection

of a Bengali mother-in-law.

Jayeeta : In Dubjaley Jetuku Prashwas novel

Manasi Burman’s excess breast milk was kept

on a table after she pumped it out. Atanu Chakraborty

who had come to visit her suddenly picked it

up and drank it. Why did he do it ?

Malay : Atanu’s mother had died recently ;

he had sexual relation for several months

with two Mizo step sisters Julie and Judy

at the Mizo capital where he had gone

for official work and was quite depressed.

When he found a mother’s milk on the

table of Manasi Burman he felt the absence

of his mother and instinctively gulped the milk.

In later novels Ouras and Prakar Parikha

I have explored the strange sexual relations

between Atanu Chakraborty and Manasi Burman,

they had by then joined the Marxist-Leninist bandwagon.

Jayeeta : How far globalization impacted Bengali literature.

Do you think that globalization is withering away ?

Malay : I can’t tell you about the current state of affairs.

These days I do not get much time to read.

We are both quite old and have to share

family activities, going to market, cleaning home,

peeling and cutting vegetables,

helping my wife in cooking etc --

I do not get much time. I have not read any novel

after introduction of globalization.

Because of Brexit and Donald Trump’s

withdrawal from international politicking globalization

has weakened ; only China is interested in selling

their products ; our markets have already been

captured by China. However, colonial Bengali

literature was possible because of Europe.

Bankimchandra started writing novels in European

form. Michael Madhusudan Dutt wrote Amitrakshar

in European form. Poets of thirties started writing

in European form, so much so that academicians

have been pointing out Yeats’ influence on

Jibanananda Das, Eliot’s presence in

Bishnu Dey’s poems. Before the British arrived,

our literary style was completely different.

Symbol, metaphor, image etc were Europe’s contribution.

I do not have much knowledge about modern songs,

but critics talk about Tagore having been

influenced by Europe, in fact some tunes

are said to be same as certain European songs.

Singing changed after arrival of Kabir Suman.

Jayeeta : There is opacity in understanding of

Remodern, Postmodern or Alt-modern

even among the poets of Zero decade.

What are the reasons ? How far Bengali literature

on the same level as that of international literature ?

Malay : Even if there is opacity in understanding

you would find influences. And it would be

incorrect to presume that everybody’s mind

is full with smoke. Some are well educated.

Some do not have any interest, they want to

write as they please. Without any understanding

of Remoden, Postmodern, Structuralism,

Poststructuralism, Feminism one may write as

he pleases. Kabita Singha did not know about

Feminist theories but she has written Feminist poems.

The type of rhymed poems being written in

Bengali commercial magazines are no more

being written in Europe, their images are

fragmentary and have speed. If one reads

the poems in Paris Review or Poetry magazine

one would find that they are being written in

easy dictions, abandoning complexities,

whereas many young poets have resorted to

complex Bengali poetry writing. The point is

that poets do not like to be branded by labels.

Everybody wants that his name should be known,

not within any arena of a label.

I myself feel disgusted because of Hungryalist label.

Most of the readers do not know beyond Stark Electric Jesus.

Jayeeta : Now let us discuss some of your personal issues.

You have written about your growing up period in

Chhotoloker Chhotobela and Chhotoloker Jubobela.

You have written about the Hungryalist period in

Hungry Kimbadanti and Rahuketu.

However, the later Malay Roychoudhury

remains unpublished for sometime.

Tell me about this period. Did you not write

or they are unpublished ? Tell us about this transitional period.

Malay : I have already written,

I have covered the entire period. In the latest issue

of Akhor little magazine I have written about the

entire period titled Chhotoloker Jibon. It is to be

published by Prativas with the title Chhotoloker Sarabela.

I have sent you a copy of Chhotoloker Jobon,

you may like to go through. Amitava Praharaj

has written that readers were purchasing this copy

of Akhor as people buy bottles of Rum before

Gandhi’s birthday, since intoxicants are not

sold on Gandhi’s birthday.

Jayeeta : What is the difference between

Malay as a person and Malay as a writer ?

How do you see yourself ?

Malay : I do not think there is any difference.

However, I have tried to destroy the image of my

identity as a person ‘Malay’ ; I am not satisfied just

by destroying the language as such. Like any other

person I go to the market, bargain during purchases,

resorted to flirting during my youth with a fisher-girl,

drink single malt in the evening. During the Hungryalist

movement I used to smoke marihuana, hashish, opium,

took LSD capsules and drank country liquor. The attire

I am in during the day is the attire I am in when

guests visit, even if they are women. I do not change

they way I talk if someone visits, though I had seen

some poets and authors talk in a peculiar limpid

way in Kolkata. Most of them are Buddhadeva Basu’s

students. I talk in Hooghly district lingo mixed

with Imlitala diction. As a person and as a writer

I belong to Imlitala, which makes it easier to break my image.

Jayeeta : Tell me about your contemporary writers

who have not been properly evaluated by Kolkata-centric

literary groups.

Malay : No evaluation is made at all and you are

talking of proper evaluation. So much cultural-political

groupism takes place that works of talented writers

and poets are not evaluated, specially fiction writers

remain neglected. Tug of war is played with literary prizes.

For the same cultural-political reasons CPM

people were driven out of Bangla Academy,

though they also were well educated and wise men.

A new bunch has come who are lavishing their dear

writers with awards. The Establishment does not

give importance to those who have avoided both sides.

For example Kedar Bhaduri, Sajal Bandyopadhyay.

Jayeeta : Has there been any change in your

consciousness after reaching life’s twilight ?

I am talking about philosophy of life.

Malay : Now I like solitude, I do not want to keep

on talking, my wife also does not like too much talking.

We do not go to celebrations.

Avoid lunch or dinner invitations, for health reasons.

Here in Mumbai, if I talk about relatives,

my wife’s cousin and her husband lives in Andheri,

who is six years older than me. Sometimes I ponder

over the problem of gathering people to take me to

the crematorium when I die. I wanted to get cremated

where my mother was cremated. Or the best thing would

be to donate the body. That depends on the condition

of the body after my death. My wife is agreeable to

this proposition. If she dies first, I also do not have

any reservation. Problem is that because of arthritis

I am not able to sign, my wife has to do it

every time when I visit a bank.

Jayeeta : Now a days your life and literary

works are subject to research and dissertation.

Readers in Kolkata want to know more about it.

Malay : It has started from about ten years back.

First Ph D was written by Bishnuchandra De and

M Phil was written by Swati Banerjee in 2007.

Marina Reza had come from USA for a research

project on the Hungryalist movement. Daniela Limonella

is working on the subject at Gutenburg University.

Rupsa Das, Probodh Chandra Dey have

written M Phil papers. Nayanima Basu, Nickie Sobeiry,

Jo Wheeler from BBC, Farzana Warsi, Juliet Reynolds,

Sreemanti Sengupta have written about our

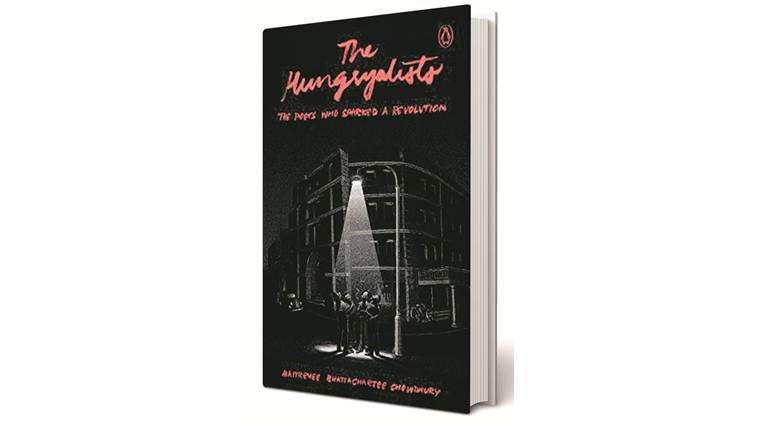

literary movement. Maitreyee B Chowdhury has written

a book titled The Hungryalists which have been published

by Penguin Random House. I know about them because

they had contacted me. Some researchers do not contact

me and approach Sandip Dutta’a Little Magazine Library

for information, such as Rima Bhattacharya, Utpalkumar

Mandal,Madhubanti Chanda, Sanchayita Bhattacharya,

Mohammad Imtiaz, Nandini Dhar, Titas De Sarkar,

S. Mudgal, Ankan Kazi, Kapil Abraham and others.

Udayshankar Verma wrote his Ph D dissertation at

North Bengal University, he did not contact me,

neither did he cover the entire literary movement.

He could have gathered more information and

documents had he contacted Dr Uttam Das.

Deborah Baker did not meet any of us nor

did she visit Sandip Dutta’s Library and wrote

abracadabra in The Blue Hand based on what

Tarapada Roy told her. Rahul Dasgupta and

Baidyanath Misra have edited a collection of

research papers and interviews titled

Literature of The Hungryalists : Icons and Impact ;

this book have photographs of all the Hungryalists.

Samiran Modak has collecte the issues of Zebra

edited by me in 1960s and published it recently ;

he is trying to anthologize all Hungryalist periodicals.

Jayeeta : You have worked in various genres of literature.

Do you have any other subject in mind to write about ?

Malay : I am thinking of writing a fiction on a Baul

couple who in their youth were involved in Naxal

movement and the other in anti-Naxal or Kangshal gang.

The fall in love after renouncing their earlier role when

they become Bauls. But I am unable to construct the

characters around them to carry the fiction forward.

The idea came after reading Faqirnama by Surojit Sen.

Since I do not have personal experience about these

mendicants I could not proceed further. Here also

the woman is elder and has more experience for

having changed partners several times. They call

themselves Mom and Dad. Sarosij Basu has

requested to write an essay on the present social

conditions of the country, nationalism, patriotism,

riots, beef eating, suppression of undercastes etc

for his periodical Bakalam,. I have started writing

under the title of Vasudaiva Jingovadam.

Problem is, I am unable to sit at the computer for long.

Jayeeta : You seem to be like Homer’s Spartan heroes.

You do not care about being attacked, people

talking against you, writing against you.

Where from do you get the life-force ? Who is your inspiration ?

Malay : Your question seems to be based on

your experience of having watched

Hollywood-Bollywood films. Is it ? Rambo,

Thor, Gladiator etc heros. I was handcuffed

and a rope tied around my waist during my

arrest for having written Stark Electric Jesus.

I was made to walk in that condition with seven criminals.

After the Khudharto group testified against

me in the Court, nothing bothers me,

lot of people of the Establishment write against me,

abuses me, specially the disciples of Khudharto group.

When I started writing, Kulsum Apa, Namita Chakraborty,

our Imlitala helping had Shivnandan Kahar and Dad’s

helper at his photo-shop introduced me to poets.

The latter two had by-hearted Saint poets

and would quote from them for scolding us.

My wife and son do not have any interest in my writing.

My daughter has but she does not have much time,

recently she suffered from a cerebral stroke as well.

I do not know whether there is really anything called

inspiration. I think I am my own inspiration, when

I walk the streets inspirations keep on getting

accumulated in my brain.

Jayeeta : Tell your devoted readers about your

present daily life.

Malay : Do you think I have devoted readers ?

I do not think so. I get up first in the morning,

wife gets up late, as she does not get good sleep

during night, takes homoeopathic medicines during

the night. After brushing I do some free hand exercise,

taught to me by the physiotherapist. Drink a glass

of lukewarm water to keep bowels clean.

Prepare breakfast, oats. Then while reclining

on the easy chair I go through The Times of India.

I do not get Bengali newspaper in our locality.

It is an area of Gujarati brokers who purchase

one Financial Times which is consulted for the

share market news by dozens of persons.

I have never invested in shares and do not

find any interest in talking to them.

If I request the hawker he will deliver four days’

Bengali newspaper in a bunch.

Then I go through the little magazines received by post.

After physiotherapy I prepare tea, green tea.

By that time my wife gets up and serves oats and fruits.

I complete my breakfast. Her breakfast is

completed around Eleven. Then I go to the market.

Fish is delivered by the shop whenever we ring them

for a particular type of fish. I do not eat meat anymore

though my wife loves it but unless you go to the butcher

you will not get good portion ; my daughter in law,

whenever she comes from Saudi Arabia on holidays,

she brings cooked meat. About eleven I sit at the desktop

and start thinking ; browse through Facebook and Emails.

Take bath at about one, have lunch with my wife,

then have a nap. From six I repeat at the desktop.

I write during this time. Now a days I am translating

foreign poets. After having dinner, take a sleeping

pill and go to bed. This the time to brood and lots

of ideas come swarming.

Jayeeta : These days poets are being categorised

in to decades ; they are being categorised on the basis

of the districts they live in as well as subjects

they specialize in. What is your opinion ?

Malay : It is a time induced phenomenon.

Time will sieve out those who are not attuned to

a particular time. The number of poets have

increased in the districts. When such anthologies

are published we would be able to have an

idea of the effects of local diction and ecology

of the space in their poems. I do not know to

which district I belong. Ancestors had come from

Jessore to Calcutta and settled at Barisha-Behala

of Calcutta. One of the descendant settled at Uttarpara

in Hooghly district in 1703, I am from his bloodline.

Now the Villa he built has been demolished and

I have sold off my portion. Then I stayed in a flat at

Calcutta’s Naktala. Thereafter came to Mumbai after

donating all my books and furnitures etc. The house I

once left, I have never gone back to live there again.

I have not spent my life in the same room, same house,

same locality, same city.

Jayeeta : Literary periodicals have now

discovered micro-poems. What is your idea about it.

Should an Editor specify the number of words or lines ?

The poet finds himself at sea in such cases.

Malay : This also has happened because of increase

in number of poets. To accommodate a large number

of poets in a particular issue of the periodical

such publications have come into vogue.

But Ezra Pound had written imagist poems

after being influenced by Chinese and

Japanese poems. He had written a poem

titled “In a Station of the Metro” which is the best

short poem ever written. Here it is:

The apparition of these faces in the crowd ;

Petals on a wet, black bough.

Jayeeta : Tell us about your international

connection, your introduction to World literature.

Have you been fascinated by any foreign

poet or writer? With whom your friendship

has been quite close ? Are they present day

foreign readers aware about your work ?

Malay : During the Hungryalist movement

I had known Howard McCord, Dick Bakken,

Allen Ginsberg, Laswrence Ferlinghetti,

Margaret Randall, Daisy Aldan, Carol Berge,

Daiana Di Prima, Carl Weissner, Allan De Loach

and others. During my arrest Police had seized

all letters which I did not get back with many books,

manuscripts and other things. These days people

from print and electronic media visit me for interviews.

BBC representatives had come for their

Radio Channel 3 and 4 programmes.

Daniela Limonella had visited a few times,

she is writing a dissertation on our movement ;

my wife also loves her. I do not know whether

you have read Maitreyee B Chowdhury’s book

“The Hungryalists” published by Penguin.

Baidyanath Misra and Rahul Dasgupta has

edited an anthology of dissertations by

academicians along with interviews of some of us.

Recently painter Shilpa Gupta visited and presented

me with sets of colours, brushes etc to enable me

to paint.I have started experimenting with colours.

In Mumbai students often visit for collecting

information. Recently a Turkish periodical has

written about me and translated my poem

Stark Electric Jesus. Turkish writer Dolunay Aker

has interviewed me which will be published in

Turkey shortly.

Jayeeta : When did you start writing poems ?

Why ? Because your elder brother Samir used to write ?

Malay : In 1958 my Dad had presented me

with a beautiful diary in which I started writing.

At that time I wrote both in Bengali and English.

Samir started writing after me. When Sunil Gangopadhyay

visited our Patna residence he evinced interest

and Samir gave him some of my poems which

Sunil published in his magazine “Krittibas”.

Later Sunil became very angry because of

the Hungryalist movement. In an interview to

“Jugashankha” Sunil had told Basab Ray that

“Malay deliberately took the opportunity as

I was in America at that time.”

Jayeeta : Without going into the details of Hungryalist

movement I would like to ask whether the poetic diction

of that time had any influence of Nicanor Parra or

Beat Generation poets ?

Malay : To be frank, till then I had not read them.

In fact I was not aware about their names.

Foreign poets meant romantic British poets.

In my poems you will find influences of Magahi

and Bhojpuri diction because of my childhood

spent at Imlitala slum of Patna. I read Beat literature

after Lawrence Ferlighetti and Howard McCord

sent me some books. Moreover all Beat prose

and poems have not been written in same style.

We in the Hungryalist movement did not follow

the same diction and style. Some of my friends

after joining CPI ( M ) party started writing in a different vein.

Jayeeta : The poems you had written during

the first phase were different from your present

day style and diction. During the first phase there

were elements of disruption. Their syntax and diction

structures were astounding. In the subsequent phase

your family life, experience have weighed

upon your work; poetry has become like deep

sea and up-wailing.

Though there is no similarity,

even then one may find out that you are the author.

Tell us something about it.

Malay : During that phase my poems had

testosterone, adrenalin. We used to fund our own

broadsides and periodical and felt free to write as we

pleased. We were in a world of drugs and Hippie Colony.

Now after having read so much and experience

of touring almost entire India, the changes have come

automatically. In between I did not write for fifteen

years and concentrated on reading.

Jayeeta : Do you think Postmodern poetry

is being written in Bengali ?

Malay : Yes, definitely. What is known as postmodern

features are seen in the poems of almost all

contemporary poets. Some young writers compose

wonderful and stunning lines and images ;

I rather feel jealous. You may read Barin Ghoshal.

Alok Biswas, Pronab Pal, Dhiman Bhattacharya.

But there are differences between postmodern

philosophy and postmodern literature.

Jayeeta : Who are the contemporary poets

you love to read, in Bengali as well as in foreign languages ?

Malay : In Bengali, Binoy Majumdar, Manibhushan

Bhattacharya, Falguni Roy, Kedar Bhaduri,

Jahar Senmajumdar, Yashodhara Raichaudhury,

Mitul Dutta, Anupam Mukhopadhyay Helal Hafiz,

Rudra Muhammad Shahidulla, Pradip Chowdhuri’s

“Charmarog” -- I am not able to remember all the

names immediately. In foreign poets I would name

Paul Celan, Sylvia Plath, Maya Angelu, John Ashbery,

Amiri Baraka, Yeves Bonneyfoy, Jaques Dupan.

I am not naming more ; you may start searching

for influences. Recently I have started translating

most of the European Surrealist poets, Arab,

Turkish and Russian poets and I am sure there

may be influences creeping in to my own poems.

Though I do not write much.

Jayeeta : Lot of research is going on about

Hungryalist movement and your work in English.

Do you feel proud about it ? Do you think you

have achieved what you had started for ?

Malay : Nothing happens to me. Those who

used to denigrate and attack me, I suppose they

feel distressed. A few days ago Kamal Chakraborty

had expressed his anguish. Actually I was offended when

Kamal agreed to publish a poetry collection of mine.

However the book was a disaster in publishing

with newsprint papers and ordinary cover

compared to his own book. But I no longer keep my books

and do not bother about them.

Publisher Adhir Biswas agreed to publish

all my books but backed out because of unknown reasons;

he also told other publishers not to publish my books.

Calcutta Literature scene has become quite dirty.

Jayeeta : Syllables or rhymes, what should be followed ?

Malay : I do not count syllables.

I write based on breath spans.

Jayeeta : You tell us to keep updated with

foreign poetry but in poetry is it not necessary

to maintain Bengali sentiment and own Bengali diction ?

If one follows foreign poetry, can it be called

copying or following ? Jibanananda Das and

many other poets had to face such complaints?

Malay : If one reads poems in other languages

one may have an idea as to in which way world poetry

is moving. There is no need to copy.

Jayeeta : In fictions, writers during Hungryalist

movement had not used local Bengali diction or

dialogoues of the marginal society. What could be the reason ?

Malay : At that time most of the writers were

Calcutta-centred. When muffassil writers started

writing marginal people and their voice entered literature.

In 1965 Subimal Basak Had written “Chhatamatha”

in Dhaka’s kutty peoples language. Rabindra Guha

and Arunesh Ghosh had also brought the lingo of

the local and marginal.

Jayeeta : In literature sexuality has entered as

Art but entirely in explicit and uncompromising way.

Readers are stunned. You people had brought

Activities of the bed and sex in creativity.

I would talk about you. Sexuality has been

highlighted in various ways, in poetry, sometimes

through characters in fiction or in memoirs,

specially in your life-based fiction “Arup Tomar Entokanta”.

Please talk about it.

Malay : Sexuality existed in Sanskrit and Bengali

literature from antiquity. During British rule, after

the Evangelical Christians poked their nose in

the syllabus of schools and colleges a new

middle class appeared and they started hesitating

with sexuality in literature. Thereafter the Brahmo Samaj

people arrived, specially Rabindranath Tagore.

When literature got out of the clutches of middle class,

sexuality in literature got its rightful place.

Jayeeta : You had proposed to your would be wife

Shalila the day after you two were introduced

and she agreed instantly ; since Shalila’s guardians

were hesitating to agree immediately, you had purchased

rail tickets to Patna to elope. But when the guardians

agreed you got married within a few days and returned

to Patna with your wife. Did you think her behaviour

to be strange for agreeing immediately.

Did your parents react annoyingly to your decision ?

Malay : No. Shalila was a field hockey player,

had reacted like a sports-girl. Moreover she did not

have her parents. She wanted to get out of the

oppressing establishment of maternal uncles.

The uncles hesitated as Shalila’s income from

her job was useful for them. If we had eloped then

there would have been problems with her job which

she did not want to quit. For getting a transfer to Patna

she required legal documents. You are a teacher,

you know how important it is for women to be financially

independent. My parents were very happy when

I reached Patna with Shalila. They thought I might become

a lout if I do not get married.

But no rituals were performed at Patna.

Jayeeta : After marriage you left your

Patna job and joined Agricultural Refinance

and Development Corporation at Lucknow,

from there you went to Mumbai to join NABARD ;

thereafter you came back to NABARD, Calcutta.

Returning after so many years did you feel that the

Hungryalist days are no more there at Calcutta ?

Malay : Only after going to Lucknow I came to

know Indian village life. Prior to that I had no idea

about cultivation, jute and cotton mills,

carpentry, handicraft, tribal life etc.

I did not know there were so many types of cattle,

pigs, goats, camels and their breeding methods.

I toured almost entire country. When I came to Calcutta,

I took along Shalila with me so that she enters the

houses of villagers to find out their way of life.

I have utilised those information in my fictions

as well as essays. What you said is correct.

When I returned West Bengal the society

had changed completely. Some critics have

written that I was in a government job.

That is not correct. The Finance Commission

increases pays and pensions of government workers

but my pension remains that same

as I am not a government worker.

Jayeeta : Do you watch Bengali serials ? Films ?

Malay : Shalila watches some serials,

but she does not stick to any one story.

If she feels a girl is not being treated properly

she shifts to another serial midway.

During dinner time I also watch with her.

Here in Mumbai there is no scope to talk

and listen to people talking in Bengali.

The Bengali serial is helpful in keeping in

touch with the way people talk in present day

Bengali. I watch short films also on my desktop

but the problem is my sound system does not

work properly ; the desktop is very old, it belonged

to my son when he was in college. Moreover

I am not able to sit continuously in front of the computer

for a long time.

I have not been to any cinema hall for about thirty years.