Talkin’ About a Revolution

The life and times of the Hungry Generation of modern Bengali poets, arguably the most dynamic and divisive literary movement of its generation

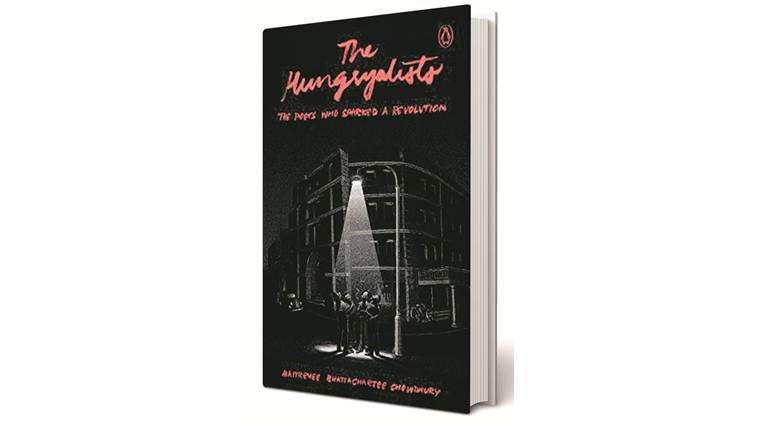

Maitreyee Bhattacharjee Chowdhury

Penguin Random House

198 pages

Rs 599

In November 1961, a one-page pamphlet, written in English and titled Manifesto of the Hungry Generation was published from 269, Netaji Subhas Road, Howrah, West Bengal. It began by stating, “Poetry is no more a civilising manoeuvre, a replanting of the bamboozled gardens; it is a holocaust, a violent and somnambulistic jazzing of the hymning five, a sowing of the tempestual Hunger.” It went on to declare, “Poetry is an activity of the narcissistic spirit. Naturally, we have discarded the blankety-blank school of modern poetry, the darling of the press, where poetry does not resurrect itself in an orgasmic flow, but words come out bubbling in an artificial muddle. In the prosed-rhyme of those born-old half-literates, you must fail to find that scream of desperation of a thing wanting to be man, the man wanting to be spirit.” Thus was born, perhaps the most debated and certainly the most divisive, “movement” in modern Bengali poetry, that of the Hungry Generation, whose founders and followers were labelled “Hungryalists”.

Three names appeared on top of that first declaration of the need for a new kind of poetic sensibility — Debi Roy (“Editor”), Shakti Chatterjee (“Leader”), and Malay Roychoudhury (“Creator”) — a fourth name, printed at the bottom, that of the publisher Haradhan Dhara, was in fact Debi Roy’s pseudonym. Missing was the name of Malay’s older brother, Samir, who was, in many ways the catalyst for the birthing of the Hungry movement, not least because he brought his friend, the poet Shakti Chatterjee, into it in the first place.

Maitreyee Bhattacharjee Chowdhury’s book is the first full-length study of the Hungryalists and it does a fine job in delineating the contours of a poetic movement whose effects on modern Bengali poetry and culture are yet to be properly evaluated, perhaps because we are still too close to the many turns and twists of the birth, development, maturity, and untimely demise, of the Hungry revolution and its protagonists for a dispassionate assessment. In her Introduction, Bhattacharjee Chowdhury makes it clear that while she will trace a chronological account of the Hungryalists, she is not going to make an attempt “at mapping every little nook and corner visited by these poets… [which] would be… an impossible task and not necessarily rewarding” and also that she will take some poetic licence with the facts because “the story of poetry found and lost is the only personal journey that survives in the end, everything else becomes a myth.”

In a 2015 documentary film on 50 years of the Hungryalist movement, the director, Tanmoy Bhattacharjee, begins by asking Malay Raychoudhury why the Hungry generation’s poetry “failed”, to which the movement’s “creator” retorts, “Who says it has failed? You? Or him? Listen, young man, the movement did not fail. What has failed is society, what has failed is literature.” The Hungryalists attempts to locate the causes of this “failure”, if indeed failure it was, as well as the enduring afterlife of a movement that had all the ingredients of a successful potboiler, with large dollops of love, sex, drugs, intrigue, backstabbing, madness, violence and politics (the Naxalite movement followed close on the heels of the Hungryalists and the split in the Communist Party of India took place whilst the Hungry movement was still on), not to speak of the imprisonment of Roychoudhury and the subsequent international outcry that led to an outpouring of support from some of the leading poets from across the globe.

This is not an easy story to tell, in large part because there are still bitter divisions of opinion regarding the roles played by some the iconic founders of contemporary Bengali poetry (Sunil Ganguly, Shakti Chattopadhyay, Sankha Ghosh, to name just three) in the Hungryalist period, all of whom have their passionate supporters wherever Bengali poetry is discussed, debated, created.

Perhaps, because she is located in a city other than Kolkata (Bengaluru) and because she is not a Bengali poet per se, Bhattacharjee Chowdhury is able to marshal her facts and put forward her opinions with the kind of dispassionate distance that someone located in the midst of the cultural churn of Kolkata’s literati would find difficult, if not impossible, to do. For which her readers should be grateful, even if they may not always agree with her sometimes glib characterisations (e.g. “Bengalis are anyway a timid race, and when attacked physically, the intellect in them is puzzled about the necessity of action”; or “Bengal was a ruin, a confused mess, and writers seemed to be its finest casualties” and analyses (e.g. her discussion of “the easing out of Buddhadeva [Bose] from Jadavpur University”. But, despite these (minor) quibbles, or, perhaps because of them, The Hungryalists: The Poets Who Sparked a Revolution should be essential reading for anyone interested in the history of modern Bengali, indeed modern Indian, poetry in the turbulent era of sex, drugs and rock and roll.

The writer is associate professor, department of Comparative Literature, Jadavpur University, Kolkata

কোন মন্তব্য নেই:

একটি মন্তব্য পোস্ট করুন