The Hungryalists: The Poets Who Sparked a Revolution

By: Maitreyee Bhattacharjee Chowdhury

Publisher: Penguin Viking

Pages: 272; Price: `599

By: Maitreyee Bhattacharjee Chowdhury

Publisher: Penguin Viking

Pages: 272; Price: `599

Oh, I’ll die! I’ll die! I’ll die!

My skin is in blazing furore

I do not know what I’ll do, where I’ll go, Oh I’m sick

I’ll kick all Arts in the butt and go away, Shubha.

My skin is in blazing furore

I do not know what I’ll do, where I’ll go, Oh I’m sick

I’ll kick all Arts in the butt and go away, Shubha.

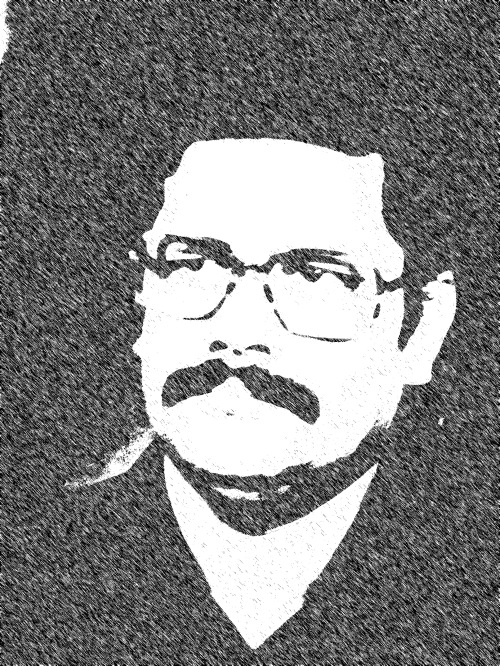

Thus begins Malay Roy Choudhury’s Bengali poem Prachanda Boidyutik Chhutar (Stark Electric Jesus). Appearing in a pamphlet in 1964, its publication resulted in arrest warrants being issued against the poet and 11 others, members of a Kolkata-based poets’ collective—the Hungry Generation. And the charges? Conspiracy against the state and literary obscenity.

Following a loose timeline, the author

dispenses with the notion of unity: anecdotes, sketches and

generalisations abound, sometimes befuddling the reader by their

randomness. However, the mood music of the age—intense, rebellious,

raucous—comes through clearly.

Though homegrown, the Hungryalists were

part of a global wave of insurrectionist poetry that had earlier seen

the rise of Beatdom in the United States. Calling the Beats and the

Hungryalists ‘co-travellers’, the author writes, ‘These poets/ writers

rejected standards of literature, introduced new societal norms, shunned

mercenaries of culture and even spawned a new drug

subculture’. Solidarity between the movements was enabled when prominent

Beat poets such as Gary Snyder and his wife Joanne Kyger, Allen ‘Howl’

Ginsberg and his lover Peter Orlovsky travelled to India and associated

with the Hungryalists.

Though

the two movements had similarities as sociocultural forces, the book

elucidates the completely different circumstances that fashioned the

Hungryalists’ poetics. The post-Partition decade of the 50s saw rapid

changes in Bengali society: a flood of refugees, homelessness, food

shortages, rising unemployment, the stench and anger of rampant poverty.

It was an all-encompassing rootlessness unrepresented in the prosaic

literary writing of the period—what Malay Roy Choudhury called ‘the

blankety-blank school of modern poetry’.

The Hungryalists wanted more: a new

lexis, a new literary space, a wider audience. Above all, a shake-up.

Their agenda was to ‘introduce chaos and a disintegration in writing

that rendered it conventionally meaningless, and take advantage of the

shock it created, thereby introducing the ideas they wanted to talk

about’. Raw emotions needed raw language: obscenity became a moral

weapon. Viewing poetry as an oral tradition, they held public readings

in Howrah railway station, College Street Coffee House, Khalasitola bar

and the grave of the long-dead Michael Madhusudan Dutt—whom the

Hungryalists idolised.

Co-authorship and collaboration being a

feature of their identity, they met regularly at ‘addas’. Another

commonality was penury: public loos, empty offices and renting space on

terraces with other homeless formed their sleeping arrangements. Despite

their travails they persisted with their poetry. The literati were

unamused; repercussions followed in the form of police raids, handcuffs,

a trial and betrayals. Nevertheless, the subaltern had found a voice

that has lasted. While the Beats are well-documented, the Hungryalists

are not. This book is a worthy attempt to fill the gap.