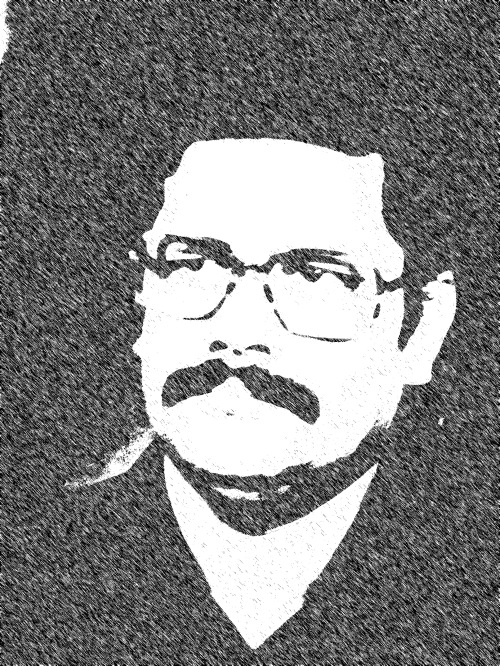

Malay Roychoudhury in Conversation with Daniela Cappello

Introducing the Poet

Malay Roychoudhury (1939) was born in Patna, Bihar, in a family of Bengali Brahmins, claiming to descend from the clan of Sabarna Roychoudhury, the zamindar family who handed over rental rights of Dihi Kalikata, Gobindapur and Sutanuti to the British in what is today’s Kolkata. Malay’s grandfather was a mobile photographer and on his sudden death at Patna his seven sons and a daughter became penniless. While Malay’s eldest uncle Pramod got a job of dusting statues at Patna Museum, Malay’s father started a photography shop. His mother was a housewife. His childhood was spent in Patna’s Imlitala slum area inhabited by low-caste ( at that time called ‘untouchables’) Hindus and poor Shia Muslim communities . His maternal grandfather was laboratory assistant to Sir Ronald Ross and the maternal uncles, who were comparatively richer and educated, stayed in Panihati, north Kolkata, the place where Samir stayed during his education at City College, Kolkata. Malay used to visit Panihati during summers to keep in touch with sophisticated Bengali language and culture. His elder brother Samir studied in Kolkata, where he befriended a group of young poets (Shakti, Sunil, Ananda, Dipak and others) with whom he shared his passion for poetry and literature. Malay joined his brother Samir in Kolkata only later. In 1961, he and other fellow poets published the Manifesto on Hungryalist Poetry from Patna, which announced the foundation of the avant-garde and anti-establishment movement the Hungry Generation. In 1961 he along with his brother Samir, Shakti and Haradhon Dhara started the movement Hungry Generation (from Patna), a group of wild and rebellious poets who were tired by the lyricism of most Bengali poetry as well as with the literary establishment that, according to their view, was bourgeois and exclusive in taste and values. The movement and its poets were arrested on charges of obscenity ( Section 292 Penal Code ) and conspiracy against the State ( Section 120B Penal Code ) in 1964. Though the rest of the writers were released, and after a trial by lower court, Malay was sentenced to either serve jail for one month or pay a fine. He lost his job. Copies of Hungryalist writings were seized by the police. He was sentenced for his poem “Stark Electric Jesus' ' which was judged obscene by the lower court magistrate. Some poets were defence witnesses at his trial, like Sunil Gangopadhyay, Jyotirmoy Datta and Tarun Sanyal. However some of his friends testified against him, like Shakti Chattopadhyay, Sandipan Chattopadhyay, Saileswar Ghose, Utpalkumar Basu and Subhas Ghose. There was national and international pressure, especially from Hindi, Gujarati and Marathi writers and the American avant garde writers and from the Beat poet Allen Ginsberg. The sentence was overturned by Kolkata High Court in 1966.

Malay has continued to write and publish collections of poems, novels, short stories and translation of poems. Since the 1990s, with his brother Samir, who edited the avant garde magazine Haowa49, he contributed to discussions on postmodernism and magical realism in Bengali. He is a prolific writer who has written about 80 books since he launched the Hungry movement. Worthy of mention are his poetry collections Shaitaner Mukh (1963), the long poem Jakham (1965 ), Medhar Batanukul Ghungur ( 1987 ) and Kounaper Luchimangsho ( 2003 ). His prose writings are mostly from the 1990s, such as the five-part postcolonial novels Dubjaley Jetuku Prashwas (1994); Jalanjali (1996); Naamgandho (1999), Ouras ( 2020 ) and Prakar Parikha ( 2021 ) reminiscent of the format and textual design of the Mahabharata, which have been defined as “the novels of rebellious counter discourse” and “a real time post-Independence socio-political nightmare”. Nakhadanta (2002), a narrative segmented into seven-day stories (drawn from Ramayana) related to the decline of the jute industry around Kolkata in particular and political violence that took place around that time. In Chhotoloker Chhotobela ( 2004 ) he has written his memoir of Imlitala days. This book has been revised to include his entire life and published as Chhotoloker Jibon in 2022. In 2003, he was awarded the prestigious Sahitya Akademi prize for his Bengali translation of Dharamvir Bharati’s Suraj ka satvan ghora but he refused it. He has translated into Bengali works by William Blake, Baudelaire, Arthur Rimbaud, Tristan Tzara, Andrè Breton, Jean Cocteau, Blaise Cendrars, Jean Genet and Allen Ginsberg as well as Arab, Uighur and Pakistani poets.. Malay’s translation of Illuminations by the French poet Rimbaud and Paris Spleen by Baudelaire have come out in early 2020.

Geographies of Youth

Question 1. Malay, you belong to a Bengali family from Patna. Your family claims to descend from Sabarna Roychoudhury family but by the time your great grandfather was born, your family had lost the lands and privileges of the title ‘roychoudhury’ – which was traditionally assigned by the Nabobs under Mughal rule – and what remained was only the name and the social history behind that title. I think that already this contradiction in narrating about yourself sums up your style and your work. How do you think Patna, Imlitala and the history of your family was significant to you and to your literary persona?

Answer 1: Though we lived in Imlitala slum, our house was full of Sabarna Roychoudhury items brought by boat from the ancestral zamindari villa at Uttarpara which has since been dismantled and a housing colony constructed in its place. Myself and Samir have sold off our share to the builder. Items brought were Iranian perfumes, very big golden frame mirrors, a mantle piece, gramophone records, silver tobacco stand, big utensils, mounted heads of tiger, deer, wolf etc and musical instruments such as organ, sitar, tabla, clarionet, harmonium etc. which reminded us of our past ancestry. My cousins, uncle Promod’s daughters, Sabu and Dhabu, used to play them before their marriage. Problem was that my father was the main earning person running the extended family of twenty members. Ancestry remained only as a miasma. What mattered was the real world of Imlitala. Uncle Pramod did not have a son ; so he purchased a baby boy from a prostitute, obviously of lower caste. Though Brahmin, our family did not prohibit us from mixing with our low caste neighbours, who were mostly petty criminals, and poor Shia Muslims, who had fled from Lucknow when the city was attacked by the British. We had no restriction on entering their houses. We brothers ate roasted bandicoots, pork meat and drank palm toddy and rice liquor, smoked cannabis at those neighbours’ festivities right from childhood. My eclectic persona and urge to rebel against restrictions was a gift from these people. Our parents did not stop us from entering Muslim houses from whom we purchased duck eggs. We also entered the local mosque to hide behind namaz mats while playing hide-and-seek. They also gave us goat legs during the celebration of Bakrid. Since uncle Pramod worked at Patna Museum, I sat behind his bicycle and visited the Museum on holidays. It was a wonderful experience for me. You just cross a door and step into prehistoric life, Mohenjodaro, Egypt or Shivaji’s Fort. I came across the dead as living beings. These were the main influences. There was no burden from my ancestry. Though a Hindu-Muslim mixed locality, there were no riots at Imlitala before, during or after partition of India. I used to roam the lanes with a cross made of two wooden planks from my Dad’s parcels and shout ‘Hip Hip Hurray’ with Imlitala urchins, like Samir’s football team, not knowing much about Christ at that time. Imlitala being an ignominious locality, Bengalis of Patna avoided visiting our house ; to them we were “Cultural Outsiders.” Bihari friends of uncles and aunts visited our house without qualms. In fact my mother and aunts did not know that the ‘Imlitala Hindi’ they were speaking was not sophisticated and some expressions were indecent. The Imlitala tap was just in front of our house ; ladies who had babies with them handed infants over to an old man who rested on the outside platform of our house, where our windows opened. This old man used to teach abuse to the infants and the infants often asked, “Grandpa, shall I tell him/her this abuse?”

Question 2. You grew up in the Patna slum of Imlitala, inhabited by Shia Muslims and Dalit Hindus alike. Your maternal uncles stayed in Panihati, north of Calcutta, and they were comparatively richer and educated, and this is where Samir was sent for study after High School and you were sent during summers to keep in touch with Bengal. What about Kolkata? What did it mean for you and your peers to move (back) to West Bengal? Do you remember having any particular “imagination” or expectation about the city of Kolkata before you reached it?

Answer 2. Firstly, nobody from our family thought of moving back to West Bengal. Samir did, when he was in his sixties, to launch his magazine ‘Haowa49’, and prove that he was not a “Cultural Outsider”. Haowa49, according to Rigveda, means Unopanshash Vayu representing fortynine storms of madness. Except for Utpalkumar Basu, all of his Krittibas friends avoided writing in Haowa49. I lived in Kolkata from time to time but not permanently. In fact I have not lived permanently in any city. Uttarpara, where we had our ancestral villa and Panihati, were pristine villages during my childhood. Compared to Imlitala, those were completely different. My maternal uncles had a huge garden with various fruit trees and two ponds full of fishes. Samir learned swimming and I learned angling as well as climbing trees. They had a library with photographs of famous Bengalis hanging on the wall. We used to visit Ahiritola, at the centre of Kolkata, from our childhood, where Aunt Kamala ( Dad’s sister) lived with her husband, six sons and two daughters. During Durga puja we visited the main Sabarna Roychoudhury house at Barisha but had a dislike for the slaughters of goats and buffaloes and their blood offered to the deity in earthen pots.. It seemed strange because at Imlitala the pigs were also slaughtered before roasting. The partition refugees did not come to Kolkata till then, when I first visited the city. No new imagination grew as I had the experience of the city whenever I went to Aunt Kamala’s house. In the late 1950s, Samir and I got disturbed when we saw hundreds of destitute refugees living at Sealdah station, through which we had to go to Kolkata city from Panihati. It created a scar in our conscience and worked as the fuse of the Hungryalist bomb against the Establishment. But I experienced real hardships of life at Kolkata during the thirty five months’ trial when I had no place to stay at night, no certainty of lunch and dinner. I had to wear the same shirt-pant for months without a bath. I used the toilets of long distance trains waiting on the Sealdah platform. The hearing at the court used to be only for ten fifteen minutes initially where I had to wait for my turn to come. I was friendless at that time and roamed the streets. I had seen the nightlife of Kolkata during that period. Aunt Kamala’s eldest son Sentu used to advice me to sleep on footpath with cheap prostitutes, in their mosquito nets. Kolkata told me in clear terms that “Malay Roychoudhury is a cultural outsider”.

Question 3. How was your relationship with your mum and dad? Do you remember it as a conflictual opposition or did you get along well? What did they do for a living, and in what way have they influenced your career as a poet, if so? What did they have to say about your poetry and your Hungryalist movement?

Answer 3. Dad being the main source of income, had no time and my mother was in charge of the family. Both of them had never gone to school. Dad was self-taught. I was much closer to my mother. She would shout from the kitchen, “read loudly so that I may hear”. She had only one anxiety that I should not become like Arun, our brother who was purchased by uncle Pramod as Arun had become a ruffian, stole items from home, fled away many times after breaking uncle Pramod’s cash-box, and secretly brought women at night when everybody slept. Arun died young and that solved everybody’s problem. Samir was sent to Panihati so that he was not influenced by Imlitala. When I was in High School Dad purchased a house at Dariapur to avoid Imlitala influence. I lived alone in that house with uncle Biswanath’s brother in law who had come to learn photography. Mother was not religious minded. Except for uncle Promod’s wife Aunt Nandarani, none of the aunts and uncles were religious minded. None of them visited temples or went on pilgrimage. I do not know why. Maybe because we could not afford it. Uncle Promod was the guardian and children were punished by him ; main punishment being a few sticks on the palm or cleaning his bicycle. After we shifted to Dariapur, Dad appreciated that I had started writing and gave me a beautiful diary ; he also told me to identify books at a local shop to deliver at home and collect payment. I had purchased a lot of English books to start my own library. Prof. Haoward McCord and Lawrence Ferlinghetti had also sent a lot of books. Since Hungryalist movement initially attracted publicity, both of them were happy that we brothers were becoming famous. When the police came to arrest me both of them were angry with them as they broke open Dad’s glass-showcase and mother’s wedding trunk, handcuffed and tied a rope around my waist while arresting me. Dad and other uncles had come to Kolkata to select a lawyer for me and Samir. Aunt Kamala’s husband used to visit the lower court to keep Dad informed. Dad had said that there was nothing to worry as I may fall back on the photography business if anything untowards happened. Dad had met the Kolkata Police Commissioner and complained about the vandalism by the policemen. The Police Commissioner had told him that they were not aware that ours was a serious literary activity. Mr. A.B.Shah, Executive Secretary of Indian Committee for Cultural Freedom had written to me on 27 January 1965, “I met the Deputy Commissioner of Police the day after we met at the office of the Radical Humanist in Calcutta. I was told that they would not have liked to bother themselves with the ‘Hungry Generation’ but for the fact that a number of citizens to whom the writings of your Group were made available, insisted on some action being taken.”

Question 4. You went to a Catholic school and then to the Ram Mohan Roy Seminary in Patna , an institution run by the Brahmo Samaj, the monotheistic religion that aimed at reforming Hinduism in colonial Bengal. We could say that even your poem “Stark Electric Jesus”, or at least its title, carries the traces of that period. Your father was an orthodox Brahmin, and you too were invested with the sacred thread ceremony. Do you think that having been brought up in religious institutions made you more rebellious or transgressive? What was your relationship with Brahmanism – in the sense of practising the rules of purity and caste hierarchy – and with the daily rituals and practises of Hindu religion?

Answer 4. The poem has several strains. The complexities of my life are included in it. My teenage and only love dominates. It took more than a month to write it. You are the first person asking this question. Nobody so far has asked what signified ‘Chhutar’ in the original poem and why it had been translated as Jesus. Yes, Samir and I had a sacred thread ceremony but we discarded the thread in a few months and did not observe the rules of Brahminism attached to it. If Brahminism had been observed by our family uncle Promod would not have purchased a baby boy from a low caste prostitute. Both the schools influenced my thinking and writing. I got admission at Catholic school because of Father Hillman, an ameteur photographer who saw me playing at Dad’s shop and got me admitted for free. At the Catholic school I had to attend Bible classes every Thursday and came to know about the story of Jesus, and that carpentry was his profession. I also came to know about Moses, Joseph, Mary Magdalene and that Jesus’s mother remained virgin. The wish to see the earth through cellophane hymen is possible only if your lover Mary is a virgin and you are in her womb. She was of snow white marble at the church which is Shubha in Bengali. Brahminisim was wiped off from life during my days at Imlitala. Kulsum Apa’s house, a Muslim girl of very dark complexion, probably having African slave blood, had intiated me into urdu poetry at Imlitala. Namita Chakraborty, the lady librarian, had introduced me to Brahmo Bengali poets and writers including Ram Mohan Roy, Shivnath Shastri, Rabindra Nath Tagore, Jibanananda Das and others. None of the schools in which I studied allowed Hindu functions. When I was urinating at the bank of the Ganges river, Allen Ginsberg shouted at me, “Hey, what are you doing ? It is a holy river !”

Question 5. You and other Hungryalists wrote a manifesto on Religion, which started with “God is Shit”. Why is that? Which God were you thinking about? How important was religion for you and for your writing?

Answer 5. Since no God existed for us, we had to attack the press whose owners had their God. I have pilloried orthodox religious views of others in my novels and stories. During my tours in villages throughout India I have seen people consider anything to be God, even a brick or piece of wood. My daughter presented to me three wooden gods of an African tribe. Kulsum Apa’s family had a flying horse made of tin which they revered. My erotic novel ‘Aroop Tomar Ento Kanta’ is based in Benaras and it deals with the city’s religious shenanigans ; even foretells the arrival of a conservative Hindu Political Party. Another novel ‘Naamgandho’ deals with a kidnapped Muslim baby girl during partition of Bengal by a refugee Communist-turned-landlord Hindu who becomes village chief. The baby girl grows up in a Hindu household and observes Hindu rituals as she is unaware of her antecedents. Her childhood lover of refugee colony days,, a Bengali Christian, who wanted to rescue her, is murdered. She never knows about her origin.

Question 6. Let us now move to sex, sexual education, porn and sexuality back in the 60s for Bengali Hindus. What kind of stuff did you have access to? Any female or male sex icon you remember from cinema? Why sex was so central in the Hungryalist early writings? Would you say it was also a metaphor for something else?

Answer 6. There was no sexual education. As a child when I visited the Museum I had seen men touching the vagina and breast of Apsaras whereas ladies touching the penis of Alexander. Continuous touches made those portions polished. When asked, uncle Promod had said, “grow up, you would know.” At Catholic school during piano class I had to stand between the legs of the piano Madam and my head touched her breasts and Do Re Mi Fa So La Ti Do resonates at the back of my head even now. At Ram Mohan Roy Seminary ( it was a coeducation school ) a friend had a small triangular mirror to look at the breasts of girls which did not excite me. Large prints of naked Apsaras used to be processed by Dad but I had become accustomed to their open breasts and vaginal slits. I first read a porn in Hindi in which the penis was the hero and recorded its adventure. The second was ‘Fanny Hill’, which I do not consider as porn. There were no porn films at that time. My ejaculations had started before I came to know of masturbation from my class fellow Subarna. He had advised that the penis should be kept clean through masturbation otherwise lints would gather as we Hindus are not circumscribed like to Jews and Muslims. My first encounter with a female body was when Kulsum Apa stood naked in their dark dirty damp room full of ducks, hens, goats and sheeps. After embracing me and finishing what she wanted to do, she declared that “you are no more a kafir.” These lines in SEJ are from the encounter with Kulsum Apa : “The surroundings of your clitoris were being embellished with coon at that time. Fine rib-smashing roots were descending into your bosom.” Then again in the poem a reference to her : “Though I wanted the healthy spirit of Aleya's fresh China-rose matrix/Yet I submitted to the refuge of my brain's cataclysm”. Aleya, as you know, means ‘jack-o-lantern’. Before I talk about my female icons, let me tell you that uncle Sushil and his Hindu priest friend Satish Ghoshal used to watch Hindi films on Tuesdays on which Dad’s shop remained closed. Dad remained busy in photographic dark room but these two persons discussed about sex of Madhubala, Nargis, Suraiya, Rehana and others. Just imagine the atmosphere of our family. Four school friends Tarun, Barin, Subarna and myself would watch English films on Sunday mornings funded by Tarun who was from a rich family. Barin had a bicycle and visited the halls to have a look at the posters and decide which film was to be watched. I was fascinated by sexual appeal of Rita Hayworth, Elizabeth Taylor, Gina Lollobrigida, Sofia Loren, Brigitte Bardot, Audrey Hepburn. Among Bengali actresses I liked Suchitra Sen and Madhabi Mukhopadhyay. Among Hindi actresses I liked Madhubala and Nargis. All older than me and dead by now. Sex for me was a challenge that posed questions around self-awareness, right from my experience with Kulsum Apa telling me “you are no more a kafir”. But she really taught me to be an infidel. It was beyond my conscious fantasies, maybe even unconscious fantasies, though sexual desire were vital components of what it meant to be adult. During my undergraduation, at Patna, prostitutes, even housewives to make quick money, used to come from other side of Ganges, around student hostels, from evening onwards ; granite slabs of a discarded graveyard were used as beds for quick sex. Biharis are more open about sex than Bengalis. Imlitala had converted me to be a Bihari. Biharis are more beatnik than American Beat writers. Even now explicit songs are sung in village weddings in Bihar, with which I have been acquainted since childhood. Each year at Imlitala, during the festival of Holi, the ladies and gents both sang explicit songs and the people became so intoxicated with palm-toddy, rice liquor and cannabis that Samir, Arun and I were warned not to venture out. But we did go out in torn clothes to enjoy the merriment. Since you know Hindi, here is an example of a song: “Daye Or Baye Ke Hile Ta Lage Better/Hai Tor Duno Indicator/Daye Or Baye Ke Hile Ta Lage Better/Hai Tor Duno Indicator/Joban Hoi Fuse Je Karbe Tu Use/Hai Chadhal Tor Jawani Chhodata Kahe Pani/Ae Rani/Hai Chadhal Tor Jawani/ Chhodata Kahe Pani.” Thus, sex was not a taboo for the Imlitala boy.

Question 7. Did age have anything to do with that (young boys in their 20s)? Or would you say that this hype about sexuality (in aesthetics and as a taboo in real life) was something rather social and historical that was rooting all over the world in those days?

Answer 7. I had only a faint knowledge of what was happening all over the world. There was no Television and Internet in those days. The newspapers were more interested in Indian news than international. Whatever I could gather was from the magazines at the British Library and USIS Library and those libraries avoided such news to be presented to Indians. Confessional poetry underlining sex had not been written till then in Bengali and to a young man from Imlitala nothing was obscene or taboo. I enraged the Cultural Guardians of Kolkata who had no idea of the lingo of even lower caste/strata of Bengalis. Their aesthetic reality was upper caste/class and different from ours. I was from Imlitala, Debi Roy from Howrah slum, Saileswar, Subhas, Pradip, Abani, Subo were from refugee families, Subimal Basak was from a family of weavers. If you go through poetry magazines of that time, you would not find low caste names therein. You might have known that the present generation of Bengali female poets write in explicit language.

Question 8. What did your wife Shalila and the other poets’ wives think about what you were writing back then? What was their role and place vis-à-vis the Hungryalist poets?

Answer 8. Shalila did not have interest in literature. She can read Bengali but can not write. When I was introduced to her by a lady named Sulochana Naidu, it was she who showed Shalila my literary activities and photographs published in Hindi magazines. She was a field hockey player when I married her. My children and even grandchildren are proud of me. Initially my blogs were started by my son. But Shalila wonders why mostly two of my poems have been recited on youtube by more than fifteen vocal artists, one is SEJ and the other one being ‘Matha Ketey Pathachhi Jotno Kore Rekho’, which translates as ‘Sending my cut-off head, please keep it safe’. Other Hungryalist writers and poets got full support from their wife. Saileswar’s wife was a poet herself. Subhas Ghose’s wife was his financial backbone. Tridib’s wife Alo was a poet and financially supported him. In fact, Tridib’s wife arranged poetry readings at various places, and edited the English magazine ‘The Wastepaper’. Pradip Choudhuri, Subo Acharya, Abani Dhar, Basudeb Dasgupta and Subimal Basak’s wife did not have any interest in literature. Arunesh Ghose’s wife knew about his activities as he was living near a brothel during his formative days. Falguni Ray did not marry. Falguni was from a zamindar family which became so poor that the members started uprooting floor and wall marble plates and sold them.

Question 9. We know that only one female poet participated in your movement – Alo Mitra, wife of Tridib Mitra. What was her role in the movement? Were there other female participants of which we don’t know about?

Answer 9. When male poets were hesitant in joining us, how can you expect female poets would join ? Saileswar’s wife Sunita had joined but that was after my trial. Female poets of my generation even now are shy of writing sex oriented poems though such poems are being written these days by young female poets. I would like to say that they are more bold than we were during our movement. About Alo Mitra’s role I have already talked about. She also edited a collection of letters written to me.

Question 10. Does it bother you when people, readers and even scholars to some extent remind you of the obscene & wild writer of Stark Electric Jesus? What is your current relationship with that poem?

Answer 10. Yes, it does. Many readers, mostly from Bangladesh, are stuck at SEJ. When they interview me or write about me they focus mainly on this poem though I have written hundreds of poems and written several novels and plays. Even young ladies are mesmerised with SEJ. I want to tell readers, please look beyond SEJ to my other works, especially essay collections on the socio-political condition of India in general and West Bengal in particular. Recently, Pooja Gupta, a painter, arranged installation of Hundred Prosecuted Poets in various cities of the world in which SEJ was included. The installation shows pierced poems on sharp rods in a dimly lit hall and voices reciting the poems one after another. SEJ to me is a double edged weapon.

Question 11. In your confessional poetry, as well as in other Hungryalist poets from the 1960s, the “male gaze” is easily recognizable. And in fact, about the Hungry Generation poetry, someone once stated that “all Hungries must prove that they are Alpha males” (who was it?). One can say confessional poetry written by male writers, as if there was a clear intention of representing the 'personal’ as a masculine “I”. Would you agree with that?

Answer 11. Yes, I agree. Miss Sreemanti Sengupta of ‘The Odd Magazine’ talked about Hungryalists trying to prove they are Alpha males. I have written poems titled ‘Alpha Female Bidalini’ and ‘Alpha Purusher Kobita’, Saileswar Ghose and Arunesh Ghose’s poems have strong ‘male gaze’ and the masculine “I”. There is nothing unethical about the “male gaze”. Greek, Roman and Hindu epics are all stories of Alpha males. In the animal world the male elephant and tiger is able to pick up the fragrance of a female in heat from ten kilometres away. Human beings have lost that power.

Question.12. Why do you think you and other Hungryalist poets were accused of “misogyny”? Do you consider yourself one?

Answer. 12 . No, I do not consider myself a misogynist. None of the Hungryalist poets were misogynist. These imputations were made by middle class Bengali academicians and not by academicians of other Indian languages in which our poems were translated. Famous Hindi writers like Phanishwar Nath Renu, Kamaleshwar, S.H.Vatsyayan Ajneya, Dharmavir Bharati wrote about us and published translated works in Hindi periodicals. Poet Nagarjun arranged to get Jakham translated and published in Hindi. Gujarati writer Umashankar Joshi wrote about us. Marathi poets Arun Kolatkar and Dilip Chitre wrote about us. Misogyny is hatred or contempt for women. It is a form of sexism used to keep women at a lower social status than men, thus maintaining the societal roles of patriarchy. People who have read my novels would not say that I am a ‘misogynist’. Even in poetry I have offered my severed head to my beloved. Several of my poems talk about the fingers or feet or eye movement of my beloved.

Question.13. How has your perception on sex and love changed in your works – from Stark Electric Jesus to later poems ?

Answer. 13. You can not stick to the same type of poetry throughout your life. It changes with reading world poetry as well as experience. Otherwise there is no use of publishing poetry collections after the first one. Love is a maddening experience. Moreover the idea sex changes with age. I had published a book titled ‘অ’, the first vowel in Bengali, in 1998, and in that book I have dissected twenty three poems of mine including the vocal speed factor in SEJ. Love is maddening, fascinating, intoxicating and sometimes disastrous. My cousin sister Meenakshi wanted to marry a Bihari non-Brahmin boy; no one in our family was agreeable - I completed the solemnization wearing a pink dhoti, yellow cotton shawl and cohl in my eyes according to their custom, at a mas marriage in a temple in Khusrupur, Bihar. My sister in law Ramola wanted to marry a non Brahmin boy for which none in Nagpur was agreeable ; I had to bring the couple to Patna and solemnise their marriage at Arya Samaj. Aunt Omiya, wife of uncle Anil was in love with a person who did not marry, went to live at Aurobindo Ashram, Pondicherry. Aunt Omiya maintained relations with him and often visited Pondicherry, an affair which imbalanced uncle Anil who became a recluse, washed his own clothes, gave up wearing shoes, ate only once a day and stopped talking to everyone except Dad. He died alone at Uttarpara weeping for aunt Omiya, who had died of breast cancer. Uncle Sunil’s daughter Puti fell in love with a boy working as a bearer at her father's catering job ; since nobody agreed, she died by hanging herself. Puti’s brother Khoka knew that his father would not agree and therefore eloped with the lower caste girl he loved and went to live at Hyderabad. The girl was brilliant in mathematics and became a famous convent teacher at Thane, near Mumbai. Samir was in love with a married lady named Gouri to whom he dedicated his first collection of poems ; in order to maintain relations with her family he married her younger sister Bela. A junior lady officer at Lucknow was in love with me and caught hold of my hand at a bus station when I was going on tour and said, “let us elope. I have told your wife that I love you.” I was stunned and convinced her that we may think over the issue calmly afterwards. She committed suicide after her marriage. Another junior lady officer at Mumbai, came to me one day and introduced herself by declaring, “you know, I do not have a uterus.” I had to avoid talking to her thenceforth. Youngest uncle Biswanath married a tenant’s daughter Kuchi at Uttarpara though granny did not approve of it, since the girl belonged to same gotra. Because of Biswanath’s threats, granny had to agree. The couple used to sleep in Dad’s studio at Dariapur ; when they left Patna and went to live at Kotrong, a hut with land, purchased by Dad, after about five years, Sentu and myself found in the trunk left by them several photographs of naked aunt Kuchi in various poses copying western artists. They were childless. Aunt Kamala’s daughter Geeta eloped with her husband’s nephew, an incident which had to be approved in a family meeting in which I was present. They did not marry, just lived-in together. Aunt Kamala’s husband committed suicide. Love has such strange getaways.

Question.14. Politics seems to be more relevant to your novels than to your poetry. We have seen your narrative shifting to economic disorder, terrorism, political scam, government corruption etc. Would you say that your poetry (or that poetry in general) is political? And if yes, how?

Answer.14. Why ? The long poem Jakham and the short poem Kamor I wrote during the Hungryalist movement were political. Jakham has been reprinted five times. Some poems in Medhar Batanukul Ghungoor, Ja Lagbey Bolben and Kounoper Luchimangsho are political. If you listen to Indian urdu poets you would know how poetry is being used as a political tool. Indian lady poet Iqrar Khalji writes and recites poems against religious restrictions. Literature in general has always been utilised to speak on important issues in a way that articulates an author’s feelings of injustice. Hungryalist movement itself was a result of Samir and my feelings about refugees on Kolkata’s Sealdah station platforms. Politics has become more relevant because of experience gathered by me during my tours in Indian villages. I have dealt with exploitation of tribals in my novels Ouras and Nongraporir Konkal Premik ; the second one is a detective love story.

Malay Roychaudhury On Writing

Question.15. You are both a poet and a prose writer, perhaps more of a poet in your youth and a prose writer in your adulthood. Would you say this is a historical shift? Do you still write poems?

Question. 15. Yes, I still write poems. I have published a total of thirteen collections in India ( the last one titled ‘Domni’ in 2020, love poems of a poet as a Baul ) and one in Bangladesh in 2019 which contains about hundred poems from various periods. A collection which includes novella, poetry, short story, translated poems, interview and analysis of my works was published in 2019. I have also written four poetic dramas. I am in search of a publisher who will publish all my poems and poetic dramas in one volume. I write prose to unburden myself of the nightmares seen by me during my tours. I have included real life incidents in some of my novels. In essays I try to present the human condition seen by me throughout India. During some of my tours in West Bengal I used to take Shalila with me so that she could enter the houses and find out the real state of the families.

Question.16. How different is it to write a piece of prose and a poem? How different is the Malay-poet from the Malay-prose writer?

Question.16. They are very different. Poems require a flash in the form of an image or line or idea or even a word ; one has to work on its diction, rhythm, images and choice of words. Earlier, when my fingers were not struck by arthritis, I used to keep a paper when I went out of home and note the ‘flash’ for using it later. For writing novels I generally think of the entire story for days together and start writing ; I keep on working on the language and structure so that I do not repeat the same. It takes several months. For essays I start writing and keep on reading on the subject.

Question.17. What kind of things do you write or like writing today?

Answer.17. I am thinking of writing a novel on the Marichjhapi massacre as a magical realist novel. Marichjhapi massacre refers to the forcible eviction of thousands of Bengali Hindu Dalit refugees who settled on forest land in Marichjhapi island in the Sundarbans, West Bengal, in 1979, and the subsequent death of hundreds refugees due to gunfire by police, rape, party atrocities, hutments set on fire, blockades and resultant starvation, and disease. Several tigers became man eaters after eating floating corpses. I shall be using real life characters and that is the reason for resorting to magic realism. Otherwise I contribute to little magazines at the request of their editor.

Question.18. Which writers/books/genres do you like reading today?

Question.18. To be frank, I do not get time to read others. I go through the little magazines sent to me and read a piece or two. We have become old and I help Shalila in cutting vegetables and cooking, loading washing machine, drying clothes etc.

Question.19. Tell us a bit about the writing process, if there is one. How do you come up with the right idea at the basis of a novel, and how do you feel it is right? How was it for you in the past? What is it that inspires you and pushes you to write?

Question.19. I have become addicted to writing. Writing has become some sort of drug. I do not drink or smoke anymore. These days I write several novels and essays in draft form at the same time. I am a loner and I write every day. My tours throughout India have enriched my stock of experience in such a way that I use incidents in my novels and essays. If a poem crops up I make a draft thereof as well , and after finishing it send it to any little magazine editor when requested.

Question.20. In the last decade, young people in India and elsewhere in South Asia have been protesting for various reasons, and especially against the conservative measures taken by the BJP government. Freedom of speech and censorship have come back to the centre of political discussion, and university campuses have been one of the main battlefields. What is your take on that, having been a censored and banned poet in the past? Is there any continuity you see in India’s censoring policy since then?

Answer.20. The censoring policy and process now has become more draconian. During Left rule in West Bengal, several plays were barred from being enacted, even famous writers like Nabarun Bhattacharya were denied permission.. Ananda Margies were burnt alive in Kolkata ; massacres took place in Nanoor, and Nandigram. I have used Rabindra Nath Tagore’s story ‘Kshudhita Pashan’ to impose on it the Sainbari killings in which the mother was fed rice soaked in her sons’ blood. The leftist strategy of territorial control, called ‘elaka dokhol’ in Bangla, by slaughtering opponents, was one of the Left’s most potent political weapons. The new menace is fascist BJP. The Bharatiya Janata Party is a steam roller party, far more dangerous, levelling all citizens into an idea of vague Hindu Nationalist ‘Indian Culture’ conceived by them. During my tour I had visited Ayodhya and what they called Ram Janmabhoomi ; I found that except for a sleeping constable on a charpoy the premises were completely empty. Now a huge temple is coming up in its place. I think because of poet Tulasidas’s Ramcharitmanas, Ram acquires an important place in the Hindi speaking population. These days reporters are murdered and cases do not reach the courts. BJP is funded by crony capitalists and most of the print and electronic media are controlled by them. Problem with fascism is that only few at the top decide and millions follow them.

Question.21. Do you think that poetry can be a means to protest?

Answer.21. Yes, it certainly can and is being used as a means of protest in various languages in India. The relationship between protest and poetry is not new in India and it goes back to before partition. This relationship can be traced back to the formation of the Progressive Writers Association in the 1930s. Hindi and Urdu language writer Premchand was made the president. Writers, poets, play writers joined the association in great numbers. Some of them included Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Saadat Hasan Manto, Ismat Chugtai, Mulk Raj Anand, Maulana Hasrat Mohani, Sahir Ludhayanvi, Kaifi Azmi, and others. Recently, Nabina Das has edited an anthology of protest poems in English titled ‘Witness - The Red River Book of Poetry of Dissent (2021)’.Telugu poet Varvara Rao, presently on bail, was in jail for a long time. In 2021 I published an anthology of poems translated by me titled ‘Anti Establishment Foreign Poets’ which includes poems of Afghan, Ugandan, Israeli, Iranian, Cuban, Uighur, Chilean, Tibbettan, Nigerian, Pakistani, French, Indian and Russian poets.

Question.22. If you could meet the young Malay in the early 60s, what would be your suggestion to him? Would you do anything differently, would you change anything?

Answer.22. Recently I saw an Anti-Establishment little magazine editor in North Bengal hired a vehicle with a loudspeaker and read out the poems and essays while moving throughout the town. He was obviously called by Police. I liked the idea and would have used the method to spread our presence throughout Kolkata and other West Bengali cities. In the 1960s our reach was limited to editors and academicians. I would have contacted young writers at district level and invited them to join. We remained Kolkata-centric and did not spread.

Question.23. In what way, with which feelings, do you look back at the Hungry Generation and at that period? Do you have any regrets?

Answer.23. My regret is that I could not prevent the insult of my parents by the Kolkata Police. Afterwards when my Dad died I could not be present ; I was on tour in Orissa at that time.