In

a city roiled by poverty, immigration, violence and the energy of

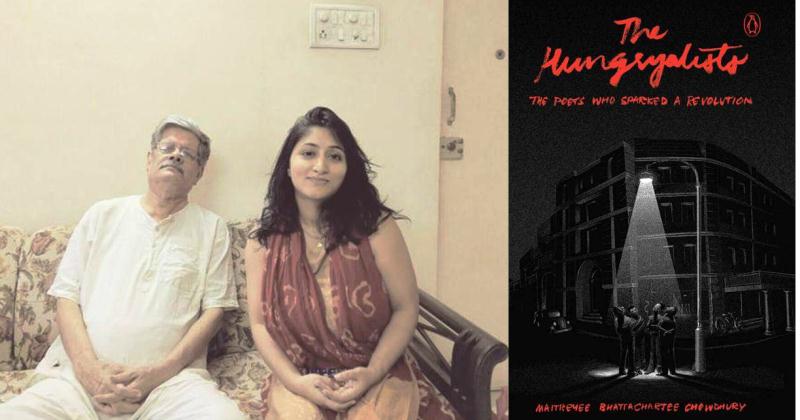

youthful anger, a new generation of writers staked their claim, says Maitreyee B Chowdhury

In October

1962, young poet Malay Roy Choudhury boarded the newly launched Janata

Express at Patna. The train would stop in Delhi before it reached

Calcutta—a rather tedious journey that would go on for over two days.

Malay hoped Calcutta would be pleasant this time of the year. His elder

brother, Samir, had written to him just before he had left for Calcutta.

You’ll reach just in time to see the city being decorated for Durga

Puja. Ma arrives in the most beautiful colours and people make the most

creative podiums for her to be worshipped in. The kashphool would have

spread its abundance. You’ll find them everywhere if you care to look,

spread out sleepily in the emptiness outside the city. The sound of dhak

will be everywhere and if you’re lucky, you’ll find some of the dhakis

at the Howrah station when you arrive. Malay wondered if Calcutta had

changed Samir. Patna was dry and without a trace of chill. The narrow

seats and the stale air that greeted him in the third-class compartment

were terrifying. He was carrying two small bags, his underwear peeking

out of one, some papers and a few packets of crisps from the other. It

was still early evening, with reluctant bogies idly basking in a gentle

sun. It was Malay’s first trip to Calcutta after the establishment of

the Hungry Generation.

Before the year would end, Malay would

meet American poet Allen Ginsberg in Calcutta. It was February 1961 when

Ginsberg landed in Bombay. A nuclear face-off had just been averted in

Cuba and Delhi was at loggerheads with Peking—a border dispute had

pushed the two countries to the brink of war. And just like everywhere

else, poets, writers and thinkers in India too were affected by these

events.

City for Poets | Calcutta ca. 1945

Ginsberg visited many places in the

country, including Benares, Patna, the Himalayan foothills and Calcutta.

During his trip, he spent most of his time mingling with like-minded

poets, musicians and artists, and later wrote about them in great detail

in his Indian Journals. In Calcutta, between keeping company

with Ashok Fakir in ‘Ganja Park’—an area near the main road stretching

from Chowringhee to Rashbehari Avenue—and hallucinating at Kali’s feet

while lying in her temples, Ginsberg would walk around the city or watch

bodies being burned in the ghats. To the ever-sceptical Bengali, he

might have seemed like just another disillusioned westerner doing the

rounds of holy Indian cities, in search of drugs, sex and ‘exotic’

spirituality. Not many Indians at the time were aware of Ginsberg’s

reputation or the influence he wielded back home. Ginsberg, of course,

had read ‘Howl’, his legendary poem, at Six Gallery in San Francisco by

then, and had begun shaping the American approach and reaction to

poetry. What effect his presence would have on the poets in Calcutta, or

they on him, time would tell vividly. But for now, he was one of them—a

poet and a wanderer, who carried with him a turbulent and disturbed

past, with the belief that here, of all places, he would be accepted no

matter how dirty or disillusioned he was.

The train moved slowly, as if struggling

with a natural inclination for inertia. Malay remembered what Samir had

written to him from Calcutta while he was in Patna. He had been angry

with their father for sending him away to Calcutta after school. The Roy

Choudhurys had decided to move from Imlitala, their Patna

neighbourhood, which their father considered a bad influence on the

boys. Pretty early on in life, the place had exposed them to free sex,

toddy, ganja, and much more. Their father had built a new house in

Dariapur and the family had shifted there. Subsequently, when Samir was

sent to Calcutta, it was a double blow for him, to be removed at once

from Imlitala and his family. Calcutta was a city he knew almost nothing

about. His instructions to Malay had been clear—he was going to live

vicariously through his brother in Patna. On certain days, Samir would

almost be pleading with Malay in his letters.

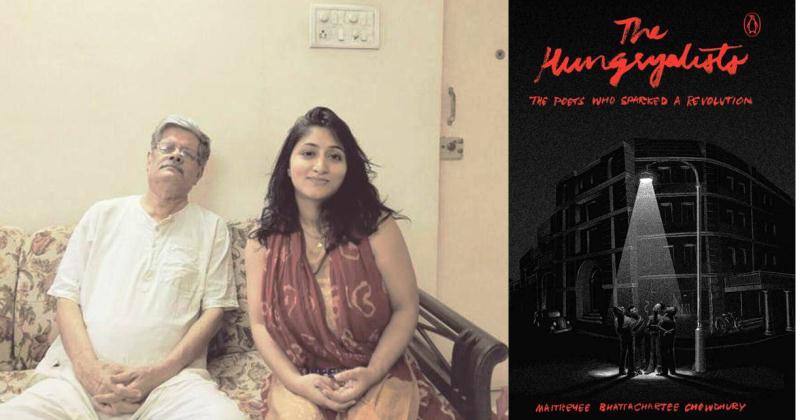

Fraternity: (Standing, from left) Saileshwar Ghosh, Malay Roychoudhury, Subhash Ghosh; (seated) Subimal Basak, David, Basudeb Dasgupta

Dear Malay,

Near

the chariali next to our house is a woman who sells bidis for two annas.

Buy a packet from her, hide it in your trunk and bring it for me when

you’re in Calcutta. Remember, nobody should know about this.

Dada

And another about a month later read:

Dear Malay,

Apparently,

there are many things to do here, but I don’t know where to start. I

have made a few friends; we meet at the Coffee House regularly. Deepak

[Majumdar], Ananda [Bagchi] and Sunil [Ganguly] are close to me.

Sometimes we discuss kobita [poetry], at other times, it is the state of

affairs. Everyone is angry here; there are strange people I meet on the

road. Theyare not like the poor of Imlitala; they have a lost look

about them. They don’t look or feel poor when you talk to them—all you

can understand is death on the inside. I think they have lost a dream.

It makes me feel horrible; I miss the easy poverty of Imlitala . . . You

must go to Bade Miyan’s paan shop at the end of our lane and tell him

about the paan that I used to have, hewill know. You could have one

yourself, but I fear it might not be good for you. You must bring one

for me though. It will cost you one anna.

Dada

Malay could not understand from Samir’s

letters whether he was happy in Calcutta or not. But he sensed some

anger. He seemed like a revolutionary without an understanding of what

his revolt was about. Malay wished Samir knew how much he wanted to see

Calcutta—this city where poems were read aloud on the streets; where a

Shankha Ghosh, even at the height of his literary career, could be

approached by college students; where Shakti Chatterjee would recite

poetry on the stairs of the Coffee House. Samir’s shift to Calcutta

indirectly helped Malay in many ways. It was Ashadh of 1952 when Malay

next received a letter from Samir. It had been raining for two days and

the blue inland envelope was wet when Malay fetched it from the

letterbox. Unlike his previous letters, Samir sounded excited in this

one—it was the first time he had forgotten to mention Imlitala.

Dear Malay,

Last

evening, Sunil, Shakti and Deepak came home. My room is small, and the

bed has too many books on it for me to move them. We sat on the terrace

adjoining my chilekothar [an attic-like room]. While it didn’t matter to

either Sunil or Deepak, I was glad I had the small mat Ma had insisted I

bring from Patna. Tha’mma doesn’t stir out of her room after dusk, so

it was OK for Sunil to bring his smoke. Thanks to the gondhoraj lebu

plant that is full of flowers and small bulbs of lemons, the smell of

smoke was confined to the terrace. We talked for a long time;

thankfully, none of them were in a hurry. Tha’mma might ask a lot of

questions tomorrow though. Sunil is full of ideas; he says he wants to

start a magazine. He is still not sure how to go about it though, but he

says he is bored of reading the same kind of writing. I told him what

you and I have talked about so many times. He seemed a bit surprised at

first, and then asked me about you. Deepak was quiet all evening, but he

sang a song later. Kaka came up to meet us. Later, he and Deepak talked

about Hindi film heroines. Their discussion made Shakti and me laugh a

lot. There was not much to eat, but Sunil had bought some pakoras on the

way; we ate them and, later, licked the plate clean. Sunil went through

my books and wanted the [Victorian poet, Algernon Charles] Swinburne

collection. I can give it to him only later, which is what I told him. I

hope he didn’t take offence though.

More later,

Dada

Many new writers were Samir’s classmates

in City College. There were other established ones, Coffee House

regulars, whom Samir had befriended and would discuss literature with.

Shakti and Sunil came up quite often; they were close friends, who had

been to his family home in Uttorpara a few times. Sunil was a prolific

and acclaimed novelist, but poetry was his first love. Indeed, Samir,

who’d recognized his talent early on, went on to fund and publish

Sunil’s first book of poems, Eka Ebong Koyekjon. Samir would

have intense discussions with Deepak, Sunil and Shakti on many an

evening on the kind of literature they had all grown up with and began

to believe in. Subsequently, he got deeply involved with Sunil in

establishing Krittibhash—a journal that launched many a Bengali poet at that time. Deepak, Ananda and Shakti were also compatriots in this venture. Krittibhash

found its voice in 1953. Samir always kept his brother in the loop, and

Malay would occasionally receive large paper packets containing

literary periodicals and books of poetry. Now as the train moved towards

Calcutta, Malay felt as if his life was coming full circle. It had been

a strange decision to visit the city at a time when post-Partition

vomit and excreta were splattered on Calcutta streets. Marked by

communal violence, anger and unemployment, the streets smelled of hunger

and disillusionment. Riots were still raging. The wound of a land

divided lingered, refugees from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) continued

to arrive in droves. And since they did not know where to go, they

occupied the pavements, laced the streets with their questions,

frustrations and a deep need to be recognised as more than an

inconvenient presence on tree-lined avenues. The feeling of being

uprooted was everywhere. Political leaders decided that the second phase

of five-year planning needed to see the growth of heavy industries. The

land required for such industries necessitated the evacuation of

farmers. Forced off their ancestral land and in the absence of a proper

rehabilitation plan, those evicted wandered aimlessly around the

cities—refugees by another name.

Calcutta had assumed different

dimensions in Malay’s mind. The smell of the Hooghly wafted across

Victoria Memorial and settled like an unwanted cow on its lawns. Unsung

symphonies spilled out of St Paul’s Cathedral on lonely nights; white

gulls swooped in on grey afternoons and looked startling against the

backdrop of the rain-swept edifice. In a few years, Naxalbari would

become a reality, but not yet. Like an infant Kali with bohemian

fantasies, Calcutta and its literature sprouted a new tongue—that of the

Hungry Generation. Malay, like Samir and many others, found himself at

the helm of this madness, and poetry seemed to lick his body and soul in

strange colours. As a reassurance of such a huge leap of faith, Shakti

had written to Samir:

Bondhu Samir,

We had

begun by speaking of an undying love for literature, when we suddenly

found ourselves in a dream. A dream that is bigger than us, and one that

will exist in its capacity of right and wrong and beyond that of our

small worlds.

Bhalobashajuriye

Shakti

Malay in Nepal

Patna, October 1961. Shakti and Haradhan

Dhara met Samir and Malay at the brothers’ newly built house. Evening

crept stealthily on to their shoulders and sat still there. The Roy

Choudhurys were still in a transitional frame of mind. The brothers had

not forgotten Imlitala—its terrific chaos, the shadows of their

childhood and their small house. The new house in Dariapur on Abdul Bari

Road looked spick and span, and stupid. “Not a house for me, not for

me!” Malay would shout at the walls. But their father would have none of

it—in his vision for his family, Imlitala was a matter of the past.

Nearby, in Rajendra Nagar, lived Hindi writers Phanishwar Nath Renu and

Ramdhari Singh Dinkar. They belonged to the Nayi Kahani and Uttar Chhaya

Wadi movements respectively—groups that believed in largely

individualistic, urbanistic and self-conscious aesthetics. While Renu

was critically acclaimed as among the most powerful and brilliant

writers of his time, Dinkar had a huge impact on readers of Hindi

poetry. He went on to become a renowned poet of national standing. His

poetry, a precursor to the A-Kavita movement, would later emerge in the

sixties as a contemporary influence, inspired in some ways by Ginsberg

and the Beat journey. Samir’s regular interactions with them would leave

a deep impact on his thinking and mould his poetry in the future.

Sometime later, Dinkar, who belonged to the community of Bhumihars,

would abandon his caste to make an important statement on caste

politics.

It was nine in the evening; dinner was

over. None of them had ventured out all day. Malay insisted that Shakti

visit Imlitala with him: “I miss Naseem Apa—her fragrant hair, the curve

of her back, the way she ran after I kissed her hazaar times in the

shadow of the imam. Shakti, come with me to see her, won’t you?” Shakti

was overwhelmed by the romanticism of a ghetto being named after a tree.

He had been eager to see the imli tree after which Imlitala was named.

“Will there be an enactment of Radha–Krishna’s sharad purnima rasa

dance?” he asked. “Did the imli tree have a golden wall after the legend

of Krishna turning a golden hue while searching for his beloved Radha,

who had disappeared in between their dance?” Malay was amused. He had

not witnessed any religion in Imlitala. Everyone born there was sworn to

poverty, their only allegiance was to the mad dance of filth around

them. He told Shakti, “Would you like to read your poetry during the

Imlitala fest? Small-time thieves, prostitutes and roadside urchins make

up the audience. Women in pink blouses and green petticoats sit down

with their men to have country liquor, one hip bent on another, and with

dirty hands touch each other. Some love will flow, some lust too.

You’ll need a different lens to be able to see this poetry.” Samir

sounded a warning that the police might be there too. “Wherever poetry

is, the dogs follow,” Malay quipped. A round of laughter followed.

Excerpted from The Hungryalists, forthcoming from Penguin India. Published in the Jan-Mar 2019 issue.