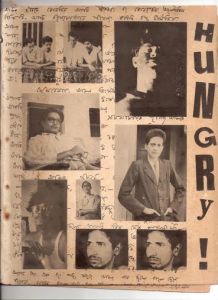

Biting more than they could chew? Problems of being too Hungry

By Titas De Sarkar

It shouldn’t surprise the readers that

the Hungryalists indulged in a ‘narcissistic spirit’ right from the

second paragraph of the first Bulletin they published, in the early

sixties. The very beginning of their existence was a self-declared one.

It was possibly the only way that they could have come into their own.

This was a backlash against the marginalised status of these poets in

the society, in the cultural field. Their lives were the result of the

tumultuous decades post the Partition of Bengal in 1947, when there was

intense displacement from both the sides of the border, an acute

shortage of space, along with a consistent rise in unemployment. The

founder members, finding no representation of these daily challenges in

the literary texts, took it upon themselves to bring the written

language up-to-date as it were, in both its form and content. It came

out as a response to a literary scene that was hijacked by middle-class

ethics, codes, and so-called pretensions. The status-quo was sought to

be maintained because of the degradation of such a lifestyle in the real

world, where joint families were replaced by nuclear ones on one hand,

and women were going out and finding their feet in the job market like

never before – more often than not against the wishes of their husbands

and fathers. Regular political rallies were organised against government

inaction and inefficiency as more and more people were becoming

disillusioned with the promises of the newly formed nation-state. It was

a time when the middle class found their cultural capital to be vastly

at odds with their unenviable economic standing. It is out of such an

asynchronous existence, that the politics of the Hungry poets emerged.

It was not only self-representational, but without the Self, the very

movement had neither an origin nor a justification. What could it be,

after all, if not being narcissistic?

A Bulletin for your thought

Representing the oppressed Self, however,

has the tendency of going overboard. A few (seven, to be specific) of

the Hungry Bulletins are going to be examined here to see if that was

indeed the case, and if so, how were they crossing such boundaries. The

fact that these specific bulletins were part of the anthology on the

Hungry Generation that was published only in 2015 is itself an

indication of how they want to project themselves, after all these

years. A manifesto is in itself a propaganda of one’s own ideas about

the world, its politics and the ideology held dear by the author,

regarding contemporary problems and the ways to counter them. Four

Hungry manifestoes out of the seven that are under consideration were

written in a point-by-point structure, presenting the agenda in the

simplest of formats. The reason for mentioning this is to point out that

the poets resorted to different tactics for letting their principles

known to the masses, rather than letting their writing speak for itself.

Does this betray their lack of confidence in the readers, who they

might have thought to be so used to the conventional reading structures

and ways of thinking, that they would be unable to grasp the politics

behind the ‘obscenities’ that these young poets were introducing to the

pages of their magazines? In any case, they were letting know of their

reasons and approaches to dissent through art in a way which was all too

familiar in the political domain, but not very much so in the artistic

circles. And that was arguably another aspect of this Hungry movement –

if the personal is political, they were bringing to the Bengali

literature, that intimate aspect of politics of the educated middle

class youth with his sexual desires, political anxieties, conflicts of

the everyday, and ways of articulation, which was not addressed till

then.

Manifestoes of the marginalised

Let us briefly look into the contents of the manifestoes. The first bulletin

credits Malay Roychoudhury as the ‘creator’, Shakti Chattopadhyay as

the ‘leader’, with Debi Roy editing and Haradhan Dhara publishing it.

Interestingly, the manifesto is in English. The poets prefer poetry to

resemble a ‘holocaust’ rather than ‘a civilizing manoeuvre’. They are

trying to overcome the ‘artificial muddle’ which is devoid of the

‘scream of desperation’. To them, most of the poems of that time were

all too glamorous, logical, and ‘unsexed’, written by individuals, who

were more concerned with self-preservation than self-doubt.

About the objectives of the Hungry movement, it is stated in the tenth bulletin

that they would put words to make silence (or, what was silenced till

then) speak. They dream of going back to the pre-civilizational chaos

and start a new world, through their creations. This will be done by

coming to terms with every sense-perception which the author possesses,

going beyond the world of comprehension. When this leads to the

self-discovery of the skeptic and vulnerable poet, he’ll cease to create

anymore.

Another bulletin, simply titled as ‘The Manifesto of the Hungry Movement’,

speaks in first person and with itself about how to write poetry. The

poet wishes to inspect himself and every aspect of his lived experience,

and question those before accepting them or otherwise. The poems should

betray precisely those moments when he was most vulnerable, so as to

get an insight into his inner self. About the linguistic signs of

poetry, the poet wishes to do away with the rhyming scheme and adopt

such colloquial words which would immediately resound with the readers.

The commonsensical placing of one word after the other would be replaced

to break the existing politics behind language, which is ‘meaningful’,

even if that leads to ‘meaninglessness’ in their creations, to begin

with.

In bulletin number fifteen,

declared as the ‘Political Manifesto of the Hungry Movement’, the

authors claim that they would liberate the very soul of the masses from

politics, because the latter is only self-serving, irresponsible and

ultimately, a fraud. No respect will be shown to a politician of any

colour. They will transform the very notion of political faith.

Bulletin numbered sixty-five is

the one related to the Hungryalist’s notion of religion. The first point

only has two words in Bengali – ‘God is garbage’. According to them,

religion makes people lose their sense of reason; it is the institution

which condones every sinful act like ‘murder, rape, suicide, addiction’,

and leads to ‘insanity’ and ‘sleeplessness’. Religion is a tool to

acquire the tangibles and intangibles of the world, and only the best of

human beings could resist the temptation of mindlessly submitting

themselves to it. It is a law unto itself, which has a parasitical

existence. It prospers only in the hearts of the faithful. Religion is

only self-glorifying.

The forty-eighth bulletin is

interesting as it talks about the role of the painter in the society,

written by two painters – Anil Karanjai and Karunanidhan Mukhopadhyay.

In true Hungry spirit, they wanted to paint those aspects of people’s

lives which aren’t highlighted due to their poor socio-economic

condition. They rue the fact that many painters let go of this principle

as their patrons belong to the elite class. Their objective would then

be to come out of this easy co-existence and spread their creation to

the masses, staying true to their ideologies. Hungry painters are free

of materialistic concerns and they consider themselves to be the

conscience of the society and ‘destroyer of evil’. To them, any

pretension in art is unforgivable.

The last bulletin to be discussed here, titled ‘Hungry

Generation’, encapsulates the meaning that poetry holds for them. Poems

written by their contemporaries do not resemble life in any way, they

regret. Moving beyond meaning-making, poems should try to explore the

chaotic, what society considers as disorder. Poems sustain these authors

despite the psychological and physical ‘hunger’ they suffer from.

Disillusioned with ‘men, god, democracy and science’, poems have become

their last resort. For them, poetry and existence have become

synonymous. However, poetry is not the escape route from the world that

has rejected them. Rather, poets could truly be liberated by giving into

their savage spontaneity. Freedom from conventional form could only be

found in the orgasmic outburst of emotions. It is therefore a call to a

culture-war against high-brow art, which is consciously made

aesthetically pleasurable, lyrically articulated, and pursued merely as a

pastime – a frivolous exercise. In contrast, poems exist to satiate the

soul of the Hungry.

Too Hungry to resist

The above claims betray certain anxieties

of the Hungry activists. There was a constant desperation to prove that

they were different from the rest, and that they were better. A

possible reaction to the judgmental society, they countered it by

examining their colleagues in turn and found them wanting, according to

their set standards. However, bringing out manifestoes and justifying

their actions is also a way of seeking validation from the masses, a

hope that they’ll be understood on some levels. Because misunderstood

they were, and the readers often looked past the politics and the

intellect behind the usage of words, which were summarily discounted as

obscene and derogatory. Yet, they believed that those very people, who

according to them were already structured by the State, societal

conventions, and ritualistic behaviour, could be capable of empathy, and

would be able to appreciate their project.

Publishing manifestoes also indicate an

expectation of winning over a section of the society in a short span of

time. Making their objectives clear would assist others to support their

cause sooner than having a prolonged investigation into their writings

and then arriving at an understanding about their work. The Hungryalists

were so few in number, that reaching out to the readers in such a

straightforward manner was probably a way to find like-minded souls.

The hyperbole which is noticed often in

these manifestoes is probably because of the huge vacuum that these

poets were trying to fill, both in the literary as well as personal

context. Taking on the entire society and its conventions is a

monumental task. When that is taken up from a marginalised position, the

articulation could cross the limits of what is humanly achievable, as

has happened here. The over-ambitious politics was also due to the

youthfulness of the authors, which has been referred to as a phase of

high optimism, a time when the protagonists are old enough to form

ideologies but young enough not to have all the responsibilities of an

adult, which gives them that impetus to see their politics through.

An interesting possibility would have

been to witness these artists doing what they did best – write or paint –

without having to justify their positions, by publishing manifestoes

and such like. But herein lies the paradox: the reason for that

justification – their poverty, lack of societal acceptance, and cultural

representation – is the very reason why the Hungry movement had come

into existence in the first place. If there was no need for any

justification, then that would have meant that the society had already

reconciled itself with their art and politics.

While the motive for coming out with

manifestoes is understandable, what remains unclear is the way of

executing the claims that the movement had committed itself to. How were

they actually going to overcome the ‘artificial muddle’? What are the

kinds of introspection that would make the poet connect with his

unconscious? Why are his words outside the conspiracy of the structures

after all, even if it breaks the known form? – all these issues require

serious engagement. Merely putting it down on paper without a definite

framework of execution only makes the words hollow. Making declarations

about liberating the soul from politics sounds rather amateurish, if not

downright problematic. One of the Hungry tactics was to consciously

make exaggerated statements through their manifestoes, poems or even

certain activities like sending masks of animals to individuals holding

important positions in the government, but such shock and awe effects

are only momentary. A detailed discussion about themes such as

uncontrolled flow of emotions or spontaneous writing could have given

one a better understanding of their ideas vis-à-vis other poets of the

world at that time. Moreover, any reader of the Bengali language would

know that quite often the words that the manifestoes had were a far cry

from the commonly spoken language of the masses. Such a convoluted way

of writing only distanced them from others.

The manifestoes show that the

Hungryalists did have the intent of trying to transform the literary

scene and in the process, the society. They did possess a few

progressive ideas, and their hearts were in the right place when they

propounded a culture for the masses, free from the trappings of elite

cultural tropes. However, the feeling one gets from the bulletins is

that they had hit above their weight. They did so knowingly, but a

spoonful of restraint, an ounce of elucidation of their propositions and

a generous helping of a vision about their long-term prospects could

have given more strength to their struggle and made it more popular. Or

maybe, they just wanted to remain Hungry forever.

কোন মন্তব্য নেই:

একটি মন্তব্য পোস্ট করুন